A Neurologic Examination for Anesthesiologists: Assessing Arousal Level during Induction, Maintenance, and Emergence

Web link: Open online

Zotero link: Open in Zotero

Tags: Anaesthesia, Depth of anaesthesia

Abstract

Anesthetics have profound effects on the brain and central nervous system. Vital signs, along with the electroencephalogram and electroencephalogram-based indices, are commonly used to assess the brain states of patients receiving general anesthesia and sedation. Important information about the patient’s arousal state during general anesthesia can also be obtained through use of the neurologic examination. This article reviews the main components of the neurologic examination focusing primarily on the brainstem examination. It details the components of the brainstem examination that are most relevant for patient management during induction, maintenance, and emergence from general anesthesia. The examination is easy to apply and provides important complementary information about the patient’s arousal level that cannot be discerned from vital signs and electroencephalogram measures.

Notes

Annotations

(7/11/2022, 10:50:19 PM)

“Guedel formalized the use of these eye signs and respiratory patterns to characterize the anesthetic state for ether , and ether used in combination with opioids.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 462)

“Although Guedel’s system no longer applies to anesthetic states created by modern techniques, anesthesiologists continue refer to the excitatory states seen at times on emergence or on induction as Guedel’s stage two.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 462)

“Patients receiving general anesthesia are placed into and brought out of a pharmacologically induced coma .6,7 This suggests that the parts of the neurologic examination that are commonly used by neurologists to assess level of arousal and integrity of brainstem and corticothalamic function in patients in coma, vegetative states, and minimally conscious states should be used to evaluate arousal levels in patients who receive general anesthesia or sedation. Use of the neurologic examination in anesthesia care would place assessments of level of unconsciousness within the same framework used by neurologists to track coma recovery.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 462)

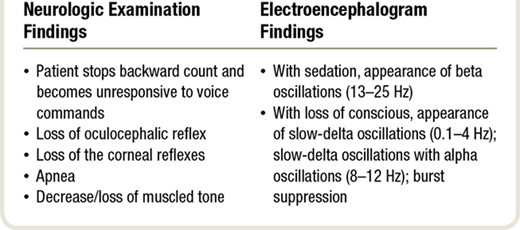

“several physiologic changes are commonly observed as the patient becomes unconscious within 10 to 30 s .

- When asked to count backwards from 100 , the patient typically loses consciousness between 80 to 90, i.e. stops counting.

- The anesthesiologist can also monitor the transition to unconsciousness by using a task called smooth pursuit , whereby the patient is instructed to track with his or her eyes the course of the anesthesiologist’s finger through space along a horizontal line.

- As the patient’s level of consciousness declines during smooth pursuit

- the lateral excursions of the eyes ↓

- blinking↑

- and nystagmus may appear.

- The eyes eventually fix in the midline as the lids close.

- Almost simultaneously, the patient becomes

- unresponsive,

- atonic,

- apneic,

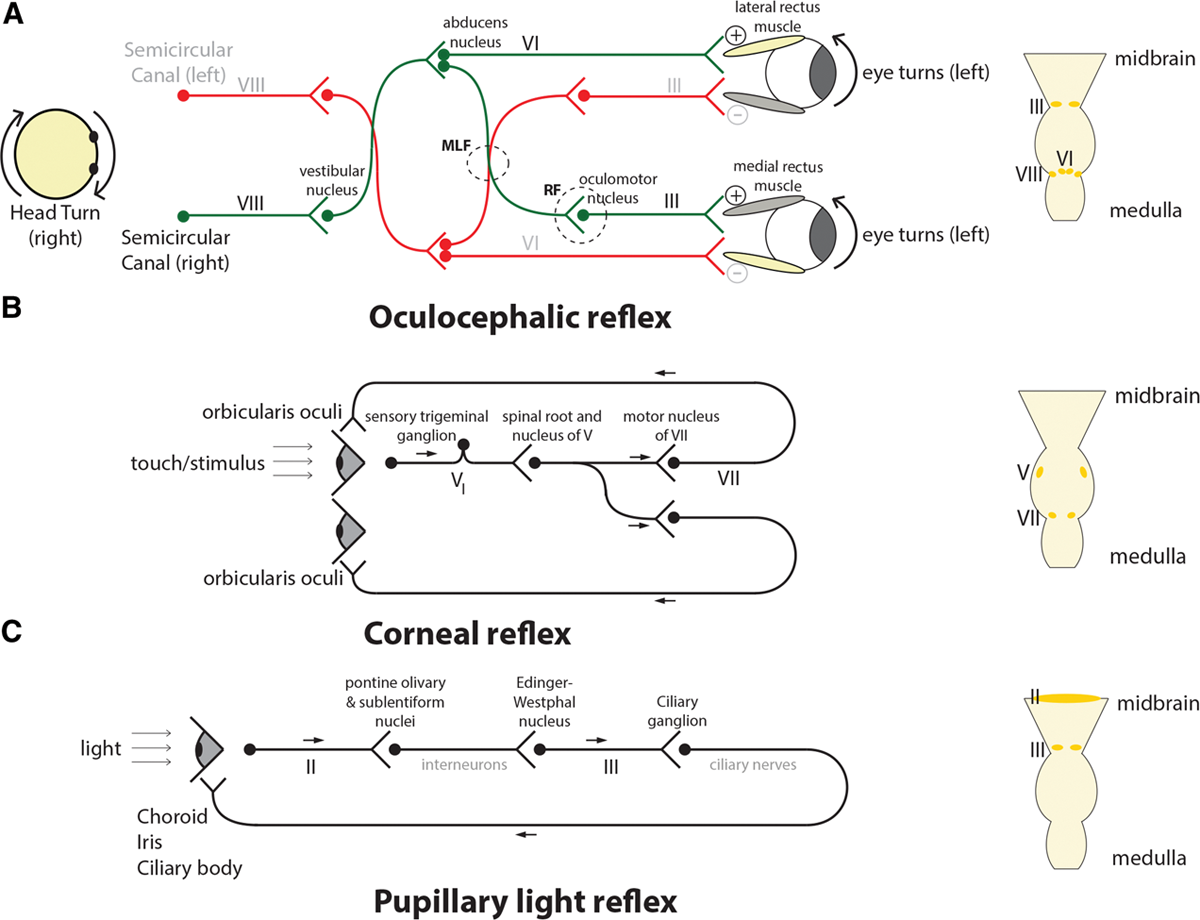

- and the oculocephalic (or more precisely vestibular-oculocephalic) (fig. 1A) and corneal (fig. 1B) reflexes are lost.

- As the patient’s level of consciousness declines during smooth pursuit

The pupillary response (fig. 1C) to light may be absent or present. At this point, unresponsiveness is interpreted as unconsciousness. It must be acknowledged that a patient could be in a state of cognitive motor dissociation . That is, conscious but unable to respond. Detecting this state would require imaging techniques and behavioral assessments not commonly used in clinical practice.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“absence of the oculocephalic reflex in the anesthetized patient suggests brainstem dysfunction whereas the absence of this reflex in a neurologically intact awake patient is normal.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“The motor nucleus of the CN6 is located in the upper pons whereas the motor nuclei of the CN3 & CN4 are located in the midbrain . Thus, failure to elicit an oculocephalic response reflects dysfunction at least along this expanse of brainstem.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“Anesthesiologists’ use of the eyelash reflex is an approximation to the more precise corneal reflex ” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“If the eyes blink consensually, the reflex is intact. If only one eye blinks, the reflex is impaired, and if neither eye blinks, the reflex is absent. The ophthalmic branch of the CN5 carries the afferent signal of the corneal reflex to the sensory nucleus of the CN5. The efferent component of the reflex emanates from the motor nucleus of the CN7. Both of these nuclei are located in the pons.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“The patient loses at approximately the same time

- consciousness

- oculocephalic and

- corneal reflexes.

The nuclei for the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, which control the oculocephalic reflex, and the nuclei of the fifth and seventh cranial nerves, which control the corneal reflex, are adjacent to the brain’s arousal centers in the midbrain, pons, and hypothalamus (fig. 2).10 Because the cranial nerve nuclei that govern these reflexes are located close to the arousal centers, it can be inferred that loss of consciousness is partially due to the anesthetic effects on the arousal centers.6,11 This statement is consistent with the neurophysiology of the brainstem and hypothalamic circuits and the pharmacology of the hypnotic agents.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“The preoptic area of the hypothalamus sends GABAergic projections to nearly all of the arousal centers .7 These anesthetics also act at GABAergic synapses in the ventral and dorsal respiratory groups of the pons and medulla, causing the apnea that commonly accompanies induction.12 The circuits of the oculocephalic and corneal reflexes are also under inhibitory control by GABAergic interneurons.13 Simultaneous action of the hypnotic agents at these GABAergic synapses explains why the changes in arousal level and apnea occur concomitantly with the loss of these brainstem reflexes.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“The atonia observed on induction can be attributed to actions of the anesthetic at multiple GABAergic sites in the motor pathways running from primary motor cortex to through the brainstem to the spinal cord. However, sites of likely brainstem action are the reticular nuclei of the pons and midbrain; lesions in these nuclei, as occur with pontine strokes, are associated with cataplexy14,15 and flaccid paralysis.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 463)

“After the hypnotic agent is administered intravenously, it rapidly reaches all parts of the brain. In particular, the agent travels through the two vertebral arteries, which fuse to form the basilar artery, the principal blood supply to the brainstem.11 Many penetrating arteries arise from the basilar artery, travel to the brainstem nuclei carrying the induction agent where it induces the observed physiologic and behavioral changes.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 464)

“As the patient becomes sedated , the unprocessed electroencephalogram shows beta oscillations (13 to 25 Hz). The beta oscillations are believed to represent primarily the effects of the induction agent on GABAergic circuits in the cortex .16 With unconsciousness , the unprocessed electroencephalogram shows profound slow (0.1 to 1 Hz) and delta (1 to 4 Hz) oscillations .The neurophysiology of these slow-delta oscillations is consistent with the anesthetics acting in the brainstem, thalamus, and cortex to decrease excitatory activity in the cortex, and hyperpolarizing thalamic and cortical circuits .17,18 The slow-delta oscillations may precede or appear at the same time as alpha (8 to 12 Hz) oscillations. Because the alpha oscillations most likely represent hypersynchronous activity between the thalamus and frontal cortex ,16,19 the simultaneous appearance of the slow-delta and alpha oscillations indicates that propofol is acting simultaneously in the brainstem, thalamus, and cortex to induce loss of consciousness.The slow-delta and” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 465)

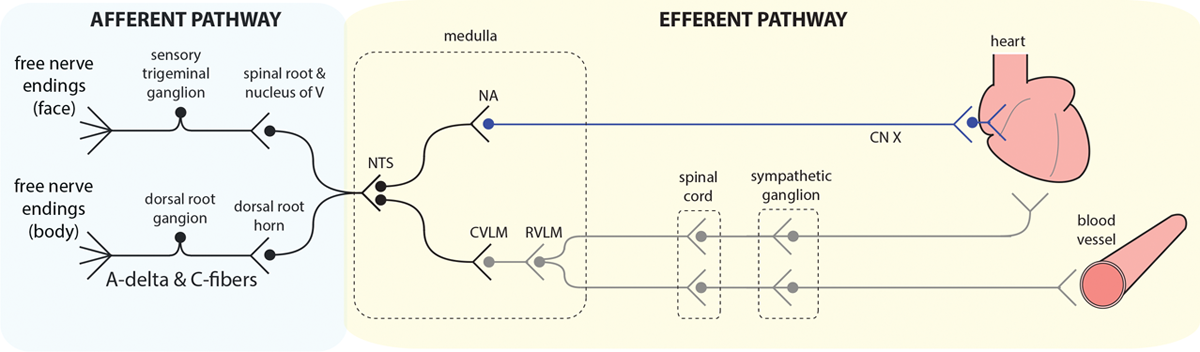

“If there is an inadequate level of general anesthesia (level of antinociception and unconsciousness) for a given level of surgical stimulation, the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure can rise rapidly. The nociceptive medullary autonomic circuit —consisting of

- spinoreticular tract

- nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the medulla

- sympathetic and parasympathetic efferents from the medulla

—can explain these physiologic changes that arise in response” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 466)

“6,21 Similarly, neurologists often assess level of arousal in brain injury patients by applying nociceptive stimuli—nail bed pinches, body pinches, or sternal rubs—to activate the nociceptive medullary autonomic circuit.10,22,23 It is imperative that anesthesiologists understand the nociceptive medullary autonomic circuit because tracking activity in this pathway is the most common method used in clinical practice to track patients’ levels of antinociception and unconsciousness.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 466)

“if movement is associated with the changes in vital signs, recovering control of nociception may be sufficient prevent further movement; however, muscle relaxation may also be needed.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 466)

“The afferent branch of the nociceptive medullary autonomic circuit begins with peripheral A-delta and C fibers that carry nociceptive information to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord where they synapse on to projection neurons (fig. 3).24 The projection neurons travel in the anterolateral fasciculus and synapse in several brainstem sites, including the nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the medulla.6,21 From the face, nociceptive information is transmitted through the trigeminal ganglia and the nucleus of the fifth cranial nerve, and then, onto the nucleus of the tractus solitarius and other brainstem sites. The nucleus of the tractus solitarius mediates the body’s sympathetic output to the blood vessels and the heart via the rostral and caudal portions of the ventral lateral medulla , which project to the thoracolumbar sympathetic ganglia.This pathway initiates the sympathetic response seen after a nociceptive stimulus.6 Furthermore, the parasympathetic outputs from the nucleus of the tractus solitarius project to the nucleus ambiguus and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus which, in turn, projects via the vagus nerve to the heart’s sinoatrial node.6 Finally, the nucleus tractus solitarius sends projections to both the periventricular and the supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus which release vasopressin .25 Hence, the nociceptive stimulus of making the incision in a patients with an inadequate level of antinociception activates the nociceptive medullary autonomic circuit, causing an ↑sympathetic activity and a simultaneous ↓parasympathetic activity that manifest as rapid ↑BP & ↑HR.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 467)

“The nociceptive stimulus is therefore sufficient to activate the nociceptive medullary autonomic pathway, but not the arousal circuits.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 467)

“Other markers of inadequate antinociception include other indicators of increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity such as perspiration, pupil dilation, and tearing, along with return of muscle tone, return of breathing, and movement.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 467)

“During general anesthesia maintained with GABAergic agents (inhaled ethers, propofol) the electroencephalogram shows strong alpha and slow-delta oscillations patterns.

In older patients (greater than 55 yr), the frequency range of the alpha oscillations tends to be lower and more narrow , and the amplitude tends to be diminished relative to young adults.18,30 In children (6 to 17 yr), the opposite is observed. The frequency range of the alpha oscillations tends to be higher and broader, and the amplitude is increased relative to young adults.18,31 That patients are unconscious when the alpha and slow-delta oscillations are present in the electroencephalogram has been well documented.18,19,32 The EEG markers of unconsciousness can be used to help distinguish between a nociceptive stimulus that produces just an autonomic response and one that produces an autonomic and an arousal response.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 467)

“Soon after the reversal of muscle relaxation, the patient regains the ability to breathe unassisted. Most patients typically begin breathing spontaneously once there is a sufficient amount of carbon dioxide in the cerebral circulation , as indicated by the end-tidal carbon dioxide level. Often the patient’s respiratory pattern is first irregular and tidal volumes are small. Within a short period of time, the pattern becomes more regular with larger tidal volumes.6 Return of spontaneous respiration signals return of function of the ventral and dorsal respiratory groups situated respectively in the caudal pons and medulla .” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 468)

“afferents that carry the nociceptive signals from the trachea, larynx, and pharynx.24 Return of salivation and tearing represents parasympathetic activity coming from the inferior and superior salivatory nuclei in the medulla and pons respectively, as well as activity of seventh and ninth cranial nerves, which carry the efferent signals.24 Grimacing indicates function in the pons, specifically the motor nucleus of the seventh cranial nerve which innervates the muscles of facial expression.24 Finally, return of the patient’s muscle tone indicates return of function in motor circuits including the primary motor tracts, the basal ganglia, the reticulospinal tract, and the spinal cord.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 468)

“The corneal reflex may return soon after or as grimacing occurs (fig. 4).6 Recovery of this reflex indicates recovery of function in the ophthalmic branch afferents of the fifth cranial nerve that project to the fifth nerve sensory nucleus, as well as in the motor efferents originating from the seventh nerve motor nucleus. Both the fifth and seventh cranial nerve nuclei lie in the pons. A consensual blink in response to corneal stimulation in one eye suggests bilateral recovery of both the motor and sensory components in the corneal reflex.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“Recovery of the oculocephalic reflex reflects a recovery of function of the third, fourth, sixth, and eighth (vestibular) cranial nerve nuclei which are responsible for eye movements.10 Because an awake patient may not show an oculocephalic reflex because voluntary control of the eyes has resumed, the best way to assess the function of these cranial nerve nuclei is to ask the patient to track the anesthesiologist’s finger in a smooth pursuit maneuver as described in the Induction section.The ability to move the eyes by voluntarily tracking the anesthesiologist’s finger indicates recovery of function in both the midbrain and pons, as well as certain cortical, cerebellar, and basal ganglia circuits. Moreover, visual tracking in the form of recovery smooth pursuit is an unambiguous sign of conscious awareness; for assessment of patients with disorders of consciousness, it is one of the most reliable signs distinguishing vegetative state from minimally conscious state in terms of nonreflexive movements.23 Recovery of function in these brain stem nuclei indirectly offers evidence that the arousal centers in the midbrain, pons, and hypothalamus have likely also recovered function” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“The pupillary light reflex may be variable as the patient recovers from general anesthesia.10 This reflex can remain intact even when a patient is deeply unconscious under general anesthesia. In contrast, the pupillary light reflex can be diminished in a patient who received a large opioid dose, yet the patient may be conscious.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“All in all, return of brainstem function during emergence from general anesthesia follows an approximate caudal-rostral progression , i.e.

- return of spontaneous ventilatory drive

- grimacing / corneal reflexes

- integrative oculomotor function

- volitional demonstrations of conscious awareness.

Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“According to the criteria that neurologists use to assess patients recovering from coma, a patient that follows motor commands inconsistently is in a minimally conscious state (fig. 4).” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“Spontaneous eye opening is often one of the last signs observed as a patient emerges from general anesthesia (fig. 4). It is possible that a patient has substantially regained motor function and is reliably responding to verbal commands, but has not yet opened his or her eyes.6 Even when patients have regained consciousness, they frequently keep their eyes closed. In contrast, a patient recovering from coma may open his or her eyes spontaneously.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“On emergence from general anesthesia maintained by GABAergic anesthetics, the electroencephalogram shows transition from alpha → beta → gamma oscillations, with a concomitant ↓ and eventual loss of slow delta oscillations.18 On the spectrogram, this transition of power across frequencies appears like a zipper opening .18 Disappearance of the slow-delta oscillations correlates with return of the brainstem functions mentioned above. The transition from, alpha to beta to gamma oscillations correlates with dissipation of thalamocortical hypersynchrony and with the patient transitioning from unconsciousness, to sedation and on to being arousable.6,16,18,19 The appearance of muscle artifact as muscle tone returns may make it difficult to read the electroencephalogram arousal patterns.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“General anesthesia is a reversible coma that is induced pharmacologically.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 469)

“The neurologic examination is also helpful for assessing the arousal state of a patient following extubation. For example, an extubated patient who follows simple verbal commands, and in particular, performs smooth pursuit, is in a much higher arousal state than a patient who only follows simple verbal commands.” Go to annotation (Reshef et al., 2019, p. 470)